References

(1) Andrady, A. L., & Neal, M. A. (2009). Applications and societal benefits of plastics. Philosophical Transactions - Royal Society. Biological Sciences, 364(1526), 1977–1984.

https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2008.0304(2) Alberghini, L., Truant, A., Santonicola, S., Colavita, G., & Giaccone, V. (2022). Microplastics in Fish and Fishery Products and Risks for Human Health: A Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 789. https:// doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010789

(3) Basic Information about Coral Reefs | US EPA. (2024, February 28). US EPA. https:// www.epa.gov/coral-reefs/basic-information-about-coral- reefs#:~:text=An%20estimated%2025%20percent%20of,including%20commercially%20 harvested%20fish%20species.

(4) Biodiversity - Coral Reef Alliance. (2021, September 1). Coral Reef Alliance. https:// coral.org/en/coral-reefs-101/why-care-about-reefs/biodiversity/

(5) Cox, K. D., Covernton, G. A., Davies, H. L., Dower, J. F., Juanes, F., & Dudas, S. E. (2019). Human Consumption of Microplastics. Environmental Science & Technology, 53(12), 7068–7074.

https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.9b01517(6) Eriksen, M., Cowger, W., Erdle, L. M., Coffin, S., Villarrubia-Gómez, P., Moore, C. J., Carpenter, E. J., Day, R. H., Thiel, M., & Wilcox, C. (2023). A growing plastic smog, now estimated to be over 170 trillion plastic particles afloat in the world’s oceans— Urgent solutions required. PloS One, 18(3), e0281596. https://doi.org/10.1371/ journal.pone.0281596

(7) Huang, L., Li, Q. P., Li, H., Lin, L., Xu, X., Yuan, X., Koongolla, J. B., & Li, H. (2023). Microplastic contamination in coral reef fishes and its potential risks in the remote Xisha areas of the South China Sea. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 186, 114399.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2022.114399(9) Pantos, O. (2022). Microplastics: impacts on corals and other reef organisms.

Emerging Topics in Life Sciences, 6(1), 81–93. https://doi.org/10.1042/etls20210236

(10) Parker, L. (2023, May 8). Microplastics are in our bodies. How much do they harm us?

Environment. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/article/ microplastics-are-in-our-bodies-how-much-do-they-harm-us

(11) Peterson, S. (2023, August 14). 6 Benefits of Plastic. RJG, Inc. https://rjginc.com/6- benefits-of-plastic/ #:~:text=Plastic%20is%20lightweight%20yet%20strong,ability%20to%20achieve%20tig ht%20seals.

(12) Plastic ingestion by people could be equating to a credit card a week. (2019, June 13). WWF.https://www.wwf.eu/?348458/Plastic-ingestion-by-people-could-be-equating- to-a-credit-card-a-week

(14) Whiting, K. (2020, February 7). This is how long everyday plastic items last in the ocean. World Economic Forum. Retrieved July 11, 2024, from https://www.weforum.org/ agenda/2018/11/chart-of-the-day-this-is-how-long-everyday-plastic-items-last-in-the- ocean/#:~:text=Depending%20on%20how%20thirsty%20you,to%20break%20down%20 the%20plastic.

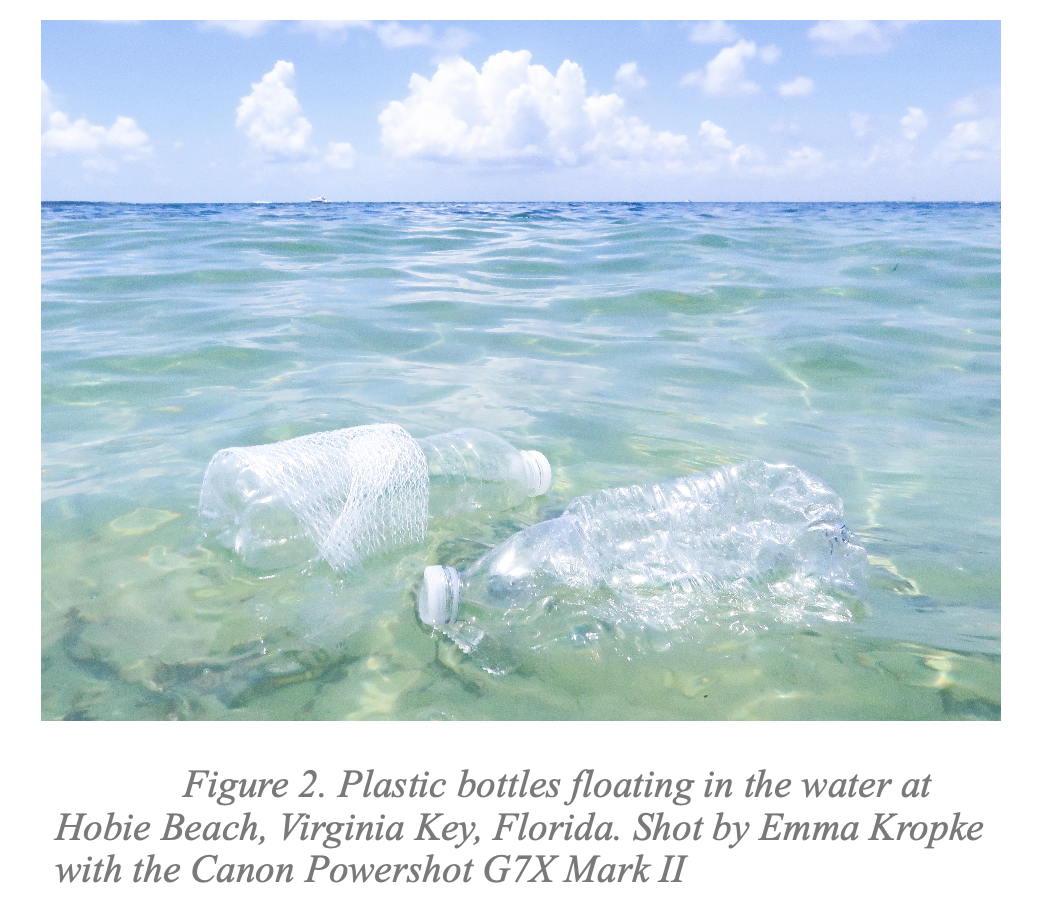

Although plastic may be the easier and cheaper option, there are significant trade-offs. Its forever-lasting existence has diminished the health of our oceans and our reefs, threatening our livelihoods. As microplastics become more prevalent, it is important to understand how individual plastic consumption, plastic waste disposal, and plastic decomposition affect what’s valuable to us. Coral reef biota and humans are being infiltrated with microplastics causing negative health effects and potentially more unknown consequences. Microplastics are here to stay, threatening not only the ecosystem but the corals themselves. It may be the beginning of understanding what this all means, but there’s still time to dismantle the plastic pollution pipeline.

Although plastic may be the easier and cheaper option, there are significant trade-offs. Its forever-lasting existence has diminished the health of our oceans and our reefs, threatening our livelihoods. As microplastics become more prevalent, it is important to understand how individual plastic consumption, plastic waste disposal, and plastic decomposition affect what’s valuable to us. Coral reef biota and humans are being infiltrated with microplastics causing negative health effects and potentially more unknown consequences. Microplastics are here to stay, threatening not only the ecosystem but the corals themselves. It may be the beginning of understanding what this all means, but there’s still time to dismantle the plastic pollution pipeline.